HS PATHOPHYSIOLOGY:

Systemic Inflammation

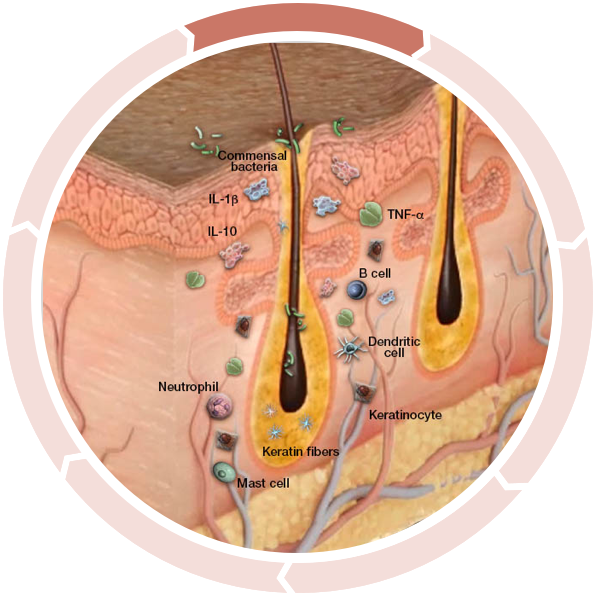

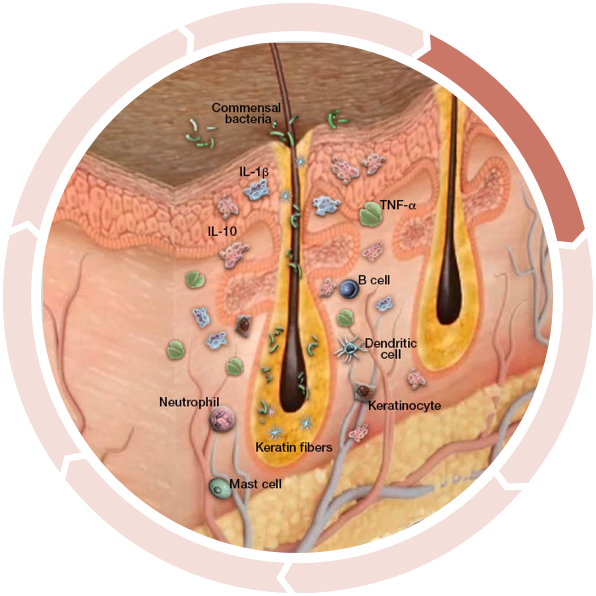

The pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is not well understood and the exact cause is still unknown, but current evidence suggests that genetic mutations, the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines, an altered local microbiome, and environmental triggers may all play a role. The apocrine glands may not be the source of HS, although the name “hidradenitis” implies it.1

It is hypothesized that occlusion, dilation, and rupture of the hair follicle, along with the resulting inflammation, lead to the symptomatology of HS.1

Cycle of Inflammation in HS

Increased inflammation activation

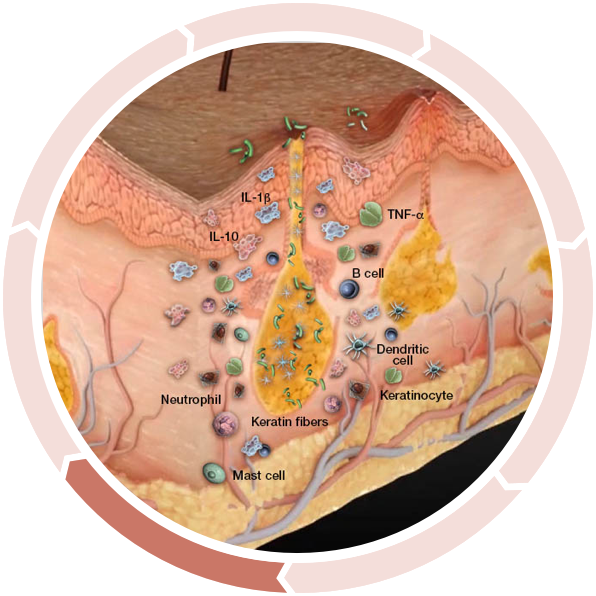

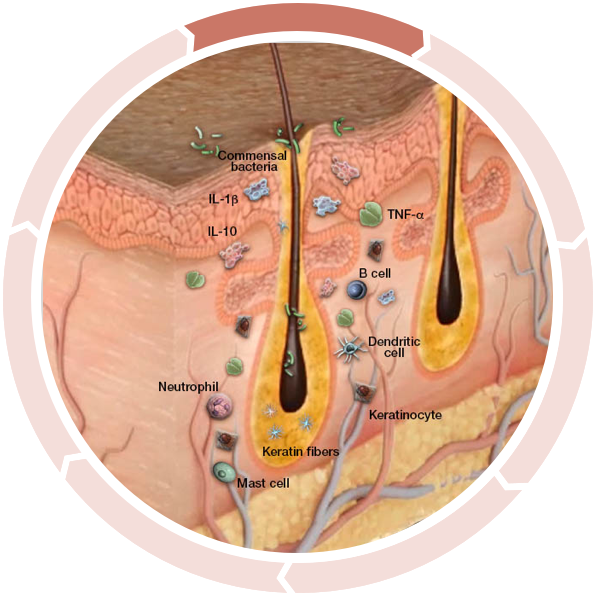

Many researchers agree the cycle begins prior to visible manifestations. Keratinocytes react to commensal bacteria (bacteria found in the skin of normal, healthy people) with an abnormal release of antimicrobial peptides as well as proinflammatory cytokines.2

Increased anti-inflammatory cytokines

Anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, are increased as a compensatory response to inflammation, attempting to limit the immune response.3,4

Altered antimicrobial peptide production

In one study, the expression of two antimicrobial peptides was shown to be significantly altered in HS lesional skin...4,5

Decreased antibacterial defense

…inhibiting antibacterial defense and allowing bacteria to persist in the dermis.4,5

Follicular Occlusion

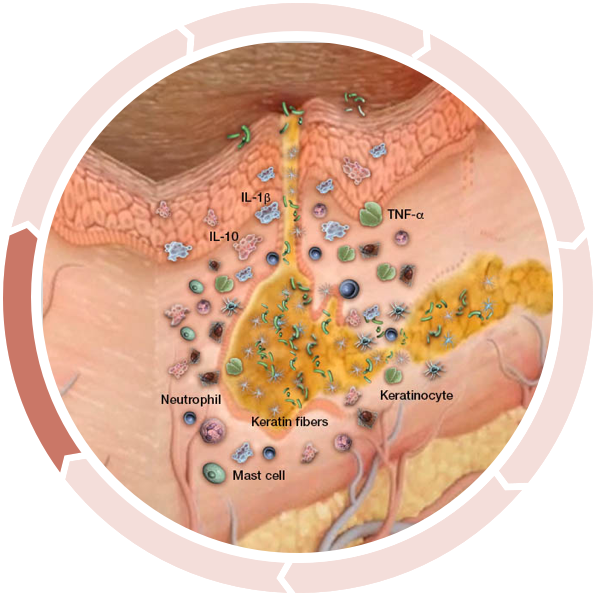

Subclinical inflammation results in epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis in the upper part of the follicle, leading to follicle occlusion and cyst formation, further accumulating commensal bacteria and propagating a chronic inflammatory response cycle.2

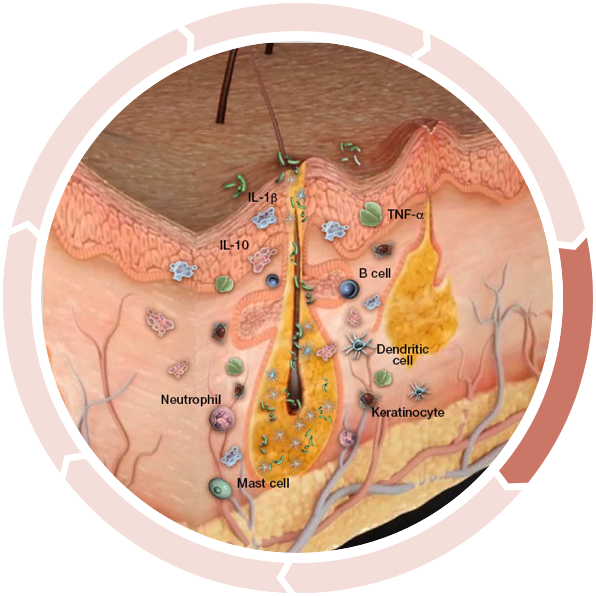

Follicular dilation and rupture

Clinical HS begins with the dilation and eventual rupture of the fragile epithelial lining of the hair follicle.2

The rupture induces massive tissue inflammation and infiltration of neutrophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, T and B cells, plasma cells, and secondary bacterial colonization, which may produce purulent discharge.2,6

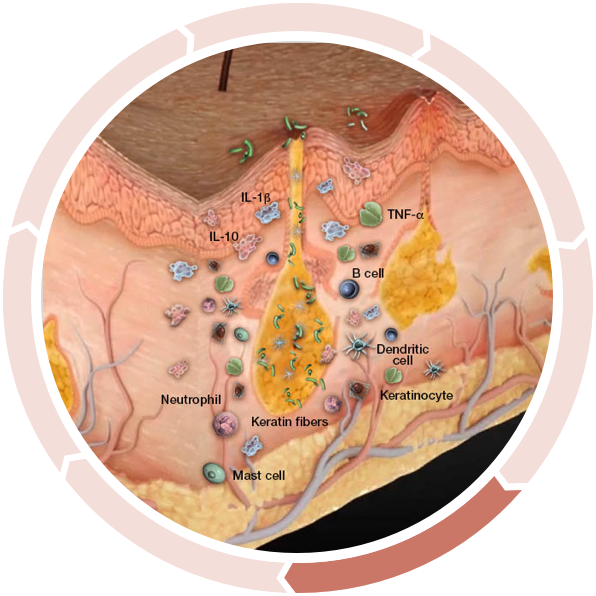

Nodule and abscess formation

A dysregulated cycle of inflammation continues, leading to spreading of the follicular plugging in surrounding nonlesional skin, rupture, and subsequent further spread of inflammation.2

Abscesses, inflammatory nodules, and sinus tracts can develop following rupture of the fragile epithelial lining of the dilated hair follicle. The resulting tunnels provide an ideal environment for bacteria, which continue to elicit inflammation, associated with purulent drainage.1,2

Clinical Manifestations

- Abscesses and nodules

- Purulent discharge

- Tissue destruction

- Sinus tracts

- Fistulas

- Scars

Increased inflammation activation

Many researchers agree the cycle begins prior to visible manifestations. Keratinocytes react to commensal bacteria (bacteria found in the skin of normal, healthy people) with an abnormal release of antimicrobial peptides as well as proinflammatory cytokines.2

See Pathogenesis of HS Develop Over Time

Dispelling Common Misconceptions of HS

Although HS awareness and education are growing, there are misconceptions about HS that may delay accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. It is important to understand what HS is not and that the disease is not the fault of the patient.

HS IS NOT CONTAGIOUS7,8

HS cannot spread by direct or indirect contact.

HS IS NOT A SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASE (STD)7

Because of the appearance and location of symptoms, HS may be mistaken for an STD.

HS IS NOT AN INFECTION7,9

Early lesions contain normal bacterial flora, suggesting that bacterial infection is a secondary feature of HS and not the cause of inflammation.

HS IS NOT RELATED TO A PERSON’S HYGIENE7,8

Poor hygiene does not cause HS.

HS IS NOT ONLY DEFINED BY ITS PHYSICAL MANIFESTATIONS6

HS can have a devastating impact on a patient’s quality of life and psychosocial well-being.

HS IS NOT CAUSED BY OBESITY OR SMOKING

Obesity - although about 50%-75% of patients with HS are obese, obesity does not cause HS. However, greater skin-fold surface area and friction, increased sweat production and retention, and hormonal changes which can lead to androgen excess are characteristics of obesity that are associated with HS. Progression and severity of disease are worse in obese patients with HS.6

Tobacco smoking - also not the cause of HS, but may contribute to disease progression and disease severity. Some studies show 70% to 88.9% of patients with HS being smokers. Nicotine may be involved in increased follicular occlusion, although the exact correlation between smoking and HS is not clear.6

“I had an HS patient with just a few nodules and slight scarring under her arm and groin. At first, I didn’t think it was that bad, but when we talked about her symptoms she said, ‘You have no idea how bad these hurt and how badly they smell.’ It made me realize I needed to do something. I was truly on the fence in treating moderate HS patients, but not anymore.”

- Dermatologist

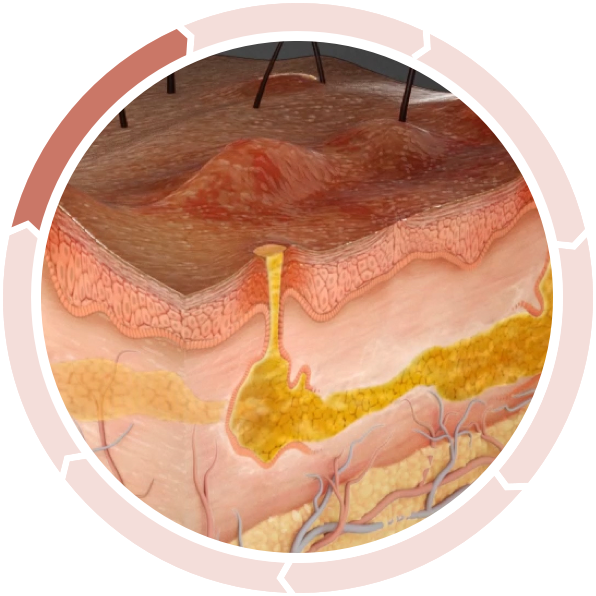

View Damage Under the Skin

Ultrasound research shows evidence of severe activity under the skin before comparable damage is visible on the surface.10,11

Discover a Treatment Option

Explore a treatment option that may be part of your management approach for your moderate to severe HS patients.

REFERENCES

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9(2965):1-12. 2. van der Zee HH, Laman JD, Boer J, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: viewpoint on clinical phenotyping, pathogenesis and novel treatments. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21(10):735-739. 3. van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, Dik WA, Laman JD, Prens EP. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)- α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1292-1298. 4. Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, et al. Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol. 2011;186(2):1228-1239. 5. Hofmann SC, Saborowski V, Lange S, Kern WV, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Rieg S. Expression of innate defense antimicrobial peptides in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(6):966-974. 6. Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):539-561. 7. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation, Inc. Accessed January 23, 2020. https://www.hs-foundation.org/what-is-hs/. 8. Kerdel FA, Menter A, Micheletti RG. What you should know about hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): information for patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33(suppl 3):S60-S61. 9. Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2019-2032. 10. Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):158-164. 11. Wortsman X, Jemec GBE. A 3D ultrasound study of sinus tract formation in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(6).